"I didn't even think that something like that could happen or that I would see what I was about to see."

Harold Bray had only turned 18 when the American warship USS Indianapolis was sunk by a Japanese submarine in the early hours of July 30, 1945.

From a crew of 1196 sailors and marines, 300 went down with their ship. Only 316 were rescued after nearly four days in the ocean. Many died from dehydration, exposure, saltwater poisoning and also shark attack – in what is believed to be the deadliest attack by the predators.

Seventy-five years after the sinking of the cruiser, Mr Bray told nine.com.au just how close he came to perishing in the greatest loss of life at sea from a single ship in the US Navy's history.

TOP SECRET MISSION

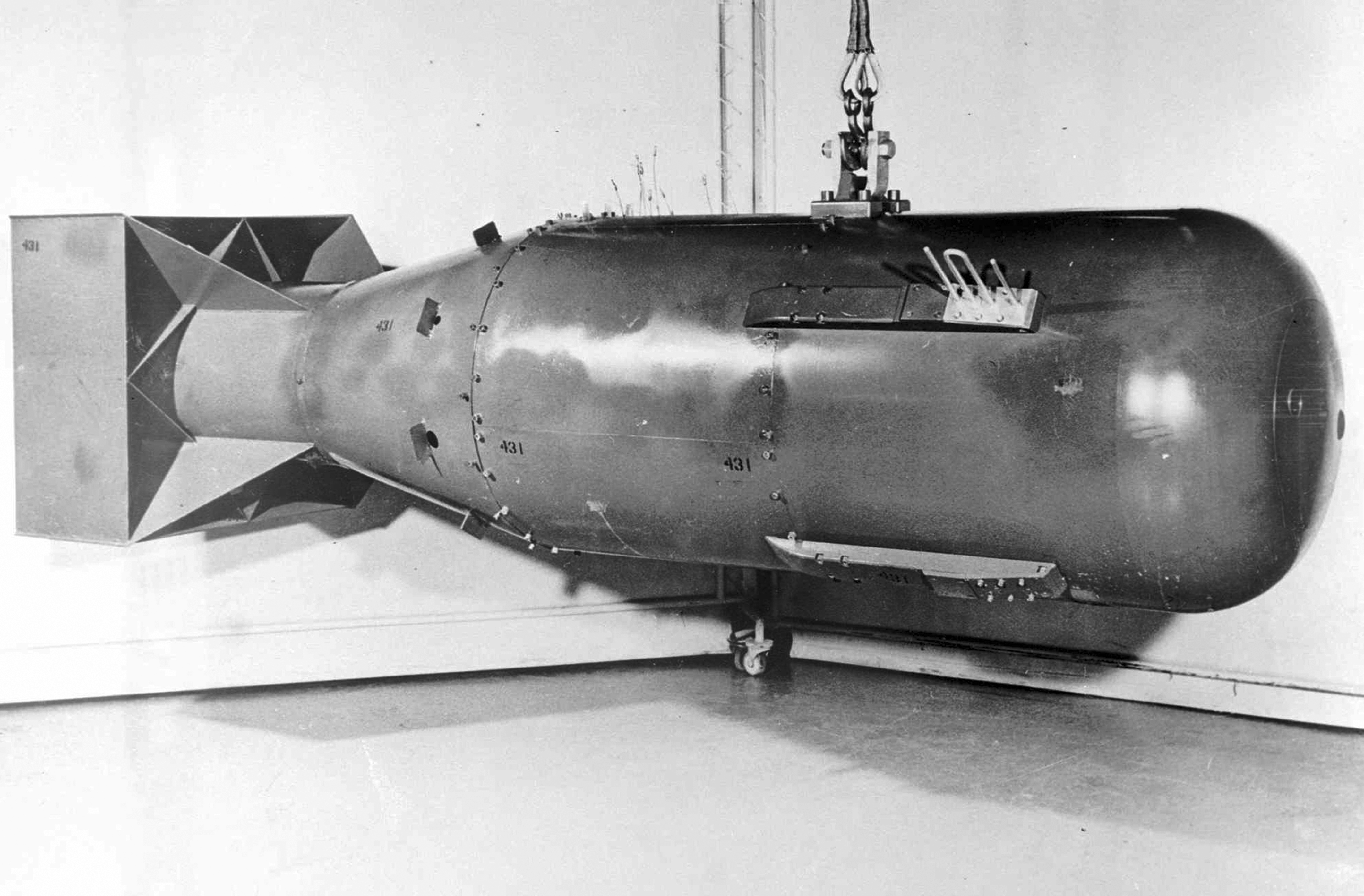

The tragedy happened just days after the USS Indianapolis completed a high-speed classified voyage to ship parts of the atomic bomb to the Pacific island of Tinian for the US Air Force.

The components were later fitted to the revolutionary weapon that was dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima just days later.

Mr Bray, 93 of California, said the heavily guarded delivery was a mystery to everyone on the warship.

"It was in the port hanger in a big box," he said.

"There were marine guards around it 24/7 and nobody knew what it was. Even the marine guards didn't know."

After leaving Tinian, the warship set out for the US-held Philippines on a voyage expected to be trouble free.

"We didn't anticipate anything. Just a routine night," Mr Bray said.

It was a view shared by US Navy chiefs: with Japan's defeat guaranteed no enemy attack was expected. Crucially, a request by the USS Indianapolis' captain for escort vessels against submarine attack was turned down.

SINKING TOOK JUST MINUTES

But the captain of Japanese Imperial Navy submarine I-58 was determined to continue the fight.

In the early hours of July 30, 1945, he spotted the US warship and after tracing it fired two torpedoes. Their effect was devastating; the torpedoes exploded under the ship's fuel tanks and tore it in half.

"I was on the midnight to 4am watch, sitting on a ledge of a 40mm gun turret," Mr Bray recalled.

"The first torpedo knocked me down about 10 feet (three metres) and I lost my shoes. I only had socks on."

About 300 men died aboard after the torpedoes struck. Mr Bray and 890 other crewmen made it into the water.

"I never learned anything at boot camp about surviving in the water. I grew up around water in upper Michigan so I knew how to swim and was comfortable in the water," he said.

It took just 12 minutes for the cruiser to sink.

ORDEAL IN OPEN WATER

But surviving the submarine attack was only the start of the ordeal for the survivors who had few lifeboats and little food or water.

After the USS Indianapolis had sunk in just 12 minutes, its engines coughed up oil that stuck to Mr Bray and many other crew. Some died after becoming engulfed in it.

Unlike many of his desperate comrades, he resisted the fatal urge of drinking sea water under the scorching sun.

"An older more experienced sailor, Pappy Goff, took me under his wing and reminded me not to drink the salt water," he said.

But the most terrifying threat came from sharks that were drawn to the area by explosions from the stricken warship.

Survivors recount the dead and wounded - seeping blood into the ocean - were the first to be taken by the predators. The aggressive oceanic white tip shark – native to the area – killed many.

Mr Bray told the Times-Herald in 2014 how he looked down under the waves and would see dozens "just swarming around us".

After devouring the dead and wounded, the predators began to attack living crewmen in the water over the three days.

Historians believe fatalities from the animals range from a few dozen to 150 men – making it the worst shark attack in history. It was famously referenced in the 1975 movie Jaws.

RESCUE CAME TOO LATE FOR MANY

Mr Bray and his crewmates were confident they would be rescued within hours, and at most a day.

But they didn't know that no distress signal was sent before the USS Indianapolis sunk. Nobody was searching for them.

Their fate was also sealed by the incompetence of senior navy commanders. It was just assumed that the warship had reached Leyte in the Philippines on its scheduled arrival date of July 31, 1945.

These factors meant the survivors had to hold on for rescue for nearly four days.

Salvation finally came on the morning of August 2, 1945 when a US Navy plane on a routine patrol flight over the area spotted men in the sea. It immediately reported the scene and a rescue mission was mounted.

But it was too late for hundreds of men. Only 316 survived.

After the war, Mr Bray received an honourable discharge from the US Navy. He then moved to Benicia in San Francisco, where he lives today.

Mr Bray is among only eight remaining survivors of the wartime disaster who will hold a virtual reunion this week.

Looking back at the ordeal, he said he is lucky to have made the milestone.

"I'm just happy to be living long enough to see the 75th anniversary," he said.

from 9News https://ift.tt/2EuhMJL

via IFTTT

0 Comments